英国诗人李道:诗歌必将是理想国际主义的

2016年10月22日 21:21

来源:凤凰文化

无论会是什么标签,当今诗歌的时代以及即将到来诗歌的时代不可分割也无可避免地会是跨文化、多文化和国际的。我把这称为想象国家的。

个人化写作与外来文化影响

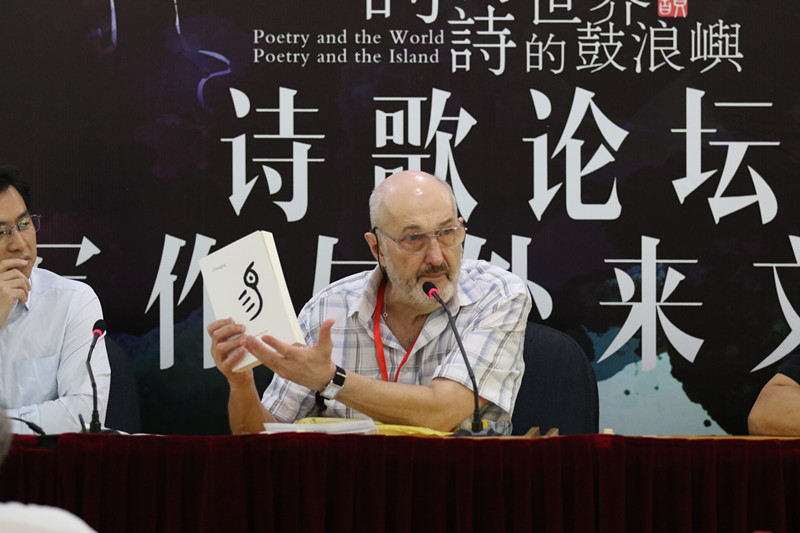

10月21日上午,2016凤凰·鼓浪屿诗歌节第二天,主题为“个人化写作与外来文化影响”的诗歌国际论坛在鼓浪屿举办。诗人赵野,赵四,李少君,树才,李元胜,默默,韩庆成,廖伟棠,林于弘、黄冈、加拿大诗人洛尔娜·克罗奇(Lorna Crozier),英国诗人李道(Richard Bruns),印度汉学学者、诗人普利亚达西·墨普德教授、韩国翻译家金泰成等人在论坛做出精彩又有见地的发言。论坛由诗人、翻译家、评论家汪剑釗和诗人北塔主持。

鼓浪屿拥有“万国建筑博览”美誉,东方文化与西方文化交会于此,闽南文化与外来文化共融于此。“鼓浪屿女婿”林语堂自评“两脚踏东西文化,一心评宇宙文章”。于诗人而言,外来文化将如何影响个人写作?作为“世界人”的诗人,一方面孜孜不倦地从自身文化中汲取养分,另一方面又无时不刻不体会着全球化带来的“文化震撼”,从而形成观念的冲突、矛盾、变形、融合、促进,进而可能形成写作的自我革新。

英国诗人李道

以下为李道的发言实录:

1.在英语表达的现代主义诗学里,国家主义者和国际主义者的倾向一直处于紧张的矛盾状态中,交织着联合与斗争:例如惠特曼、庞德、威廉·卡洛斯·威廉斯、叶芝、艾略特、麦克迪米德。但时至当下,从达达运动发端于瑞士的苏黎世迄今整整一百年里,现代主义早已是死亡。至于后现代主义(无论那个术语可能曾经意味着什么),它已经胎死腹中。那两个术语——或者口号——怎么说都相当愚蠢。而今我们站立在一个新诗学时代的黎明中,不过这个时代我们还没有名称。或许这样更好,因为我们已经变得厌倦并且怀疑口号。在近几个时期,艺术家和诗人没有创造多少这些东西,它们更多的是由学者型专家、新闻从业者和社会学家们发明,而这些人总是迟到,太迟进入这个领域,无论他们认为他们是多么迅捷。

2.在这后五十年里,我自己的文学实践已经确定在国际主义上。我曾经生活在希腊、意大利、美国和前南斯拉夫。我的许多著作就受启发于那些国家的文学、文化、历史、地理、以及地理心理。最近,我的最新作品《易》(CHANGJING,曾译作《改变》和《变迁》)(2016年9月才刚刚出版)正是向中国文化、向中国诗学和哲学传统的致敬之作。这部作品植根于典籍《易经》(英文译作《易经》或者《易经,变化之书》)。《易经》架构起并且规范了我的作品,您可以把它当做一本包括450首短诗的诗歌集来读,也可以把它看作是一首包含了450个部分的长诗。《易》既是依据也是源于这部中国古代的伟大作品,尽管我是说英语的人、对汉语只知道那么一点点。这是如何可能?因为,经过被其它语言的众多翻译和评注之后,《易经》已经成为属于全人类的著作,而不仅仅是为中国人所拥有的珍藏。如果语言正统论者主张,“你如若不说汉语,你甚至都不能读,更不要说理解《易经》”,我的质朴回答就会是:“我能读能理解圣经,即便是我不懂古希伯来语、阿拉米语或者希腊语。国王詹姆斯的《钦定本[圣经]》(1611)本身就是经典。”显而易见,不能低估在诗歌世界里翻译的至关重要。

3.今天,主要得益于信息技术,世界上所有的文化、文学和诗学传统,作为我们正当而有意义的遗产之一部分,对我们所有人而言都是开放的、可以获取并且可以利用的。所以当今写作的一位中国诗人可能会受到比如《吉尔伽美什史诗》、约翰·济慈、亚瑟·兰波、玛丽娜·茨维塔耶娃、保罗·策兰、托马斯·特朗斯特罗姆或者加里·施耐德的影响——而依然保持并信守他或她完全的中国身份——就像我,一个英国诗人一样,能够受到《易经》、《道德经》、荷马、李白、杜甫、奥克塔维奥·帕斯、乔治·塞菲里斯、伊曼努尔·列维纳斯和伊万·拉里奇的影响。因而,我们这个当代的形势不仅是微妙而有趣的复杂,也是充满活力、令人兴奋而又洋溢潜能的。

4.从这个意义上说,我们所有人都既是本土的又是域外的。在世界上绝大多数主要城市里都可以找到说汉语的人。说希腊语、阿尔巴尼亚语、斯瓦西里语、孟加拉语以及数百种其他语言的人群,无论大小也都是如此。如今在伦敦的学校里,人们说着超过三百种的语言。因此每一种文化至少潜在地都有它的离散,每一种语言都是国际性的。如果真是那样,那么(它的)诗歌也是如此。这样,诗歌中什么是本土的、什么是外来的(异质、他者、外国、奇异、等等)这个问题的确需要重新诠释。一棵苹果树在四川的果园与在诺曼底或者伊利诺伊或者布宜诺斯艾利斯一样可以长得好,它的果实也一样独具个性、一样甜美。世界的历史充满文化的再传播和语言的迁移,就像是植物的移植。

5.基于所有这些理由,对于一个要对语言和文学影响开放而不是囿于他或她自己祖先传统的诗人来说,从来不需要暗示个性和文化身份的丢失,相反,那是一种丰富和深化。所有的文学都是一个文学之一部分。所有的诗歌都是一个诗歌之一部分。所有的人类文化都属于共同和一致。我们全都是不断加深和拓宽的奔腾洪流之一部分,这个奔腾洪流英国浪漫主义诗人威廉·华兹华斯称之为“人类音乐”。

6.所以,无论会是什么标签,当今诗歌的时代以及即将到来诗歌的时代不可分割也无可避免地会是跨文化、多文化和国际的。我把这称为理想国际主义的。

Imaginationalism

Anextract from a longer statement

Richard Berengarten

(Li Dao)

1. In Anglophone poeticModernism, nationalist and internationalist tendencies were in constanttension, alternately combining and struggling: Whitman, Pound, William CarlosWilliams, Yeats, Eliot, MacDiarmid. But by now, exactly one hundred years sincethe Dada movement started in Zürich, Switzerland, Modernism is long dead. Asfor Postmodernism (whatever that term may have meant), it was stillborn. Bothof those terms – or slogans – were pretty silly anyway. Now we stand at thedawn of a new poetic age, for which as yet we have no name. Perhaps it isbetter that way, because we have grown tired and suspicious of slogans, whichin recent times have been invented not so much by artists and poets as byscholarly experts, journalists and sociologists, who come always late, toolate, into the field, however quick they may think they are.

2. For the last fiftyyears, my own literary practice has been decidedly international. I have livedin Greece, Italy, the USA and former Yugoslavia. Many of my books have beeninspired by the literatures, cultures, histories, geographies, andpsycho-geographies of those countries. Most recently, my latest book, Changing (just published in September2016) is a homage to the Chinese cultural, poetic and philosophical tradition.This book is grounded in the classic, the Yijingor I Ching, the Book of Changes. The Yijingstructures and frames my book, which may be read either as a collection of 450short poems, or as a single long poem consisting of 450 parts. Changing both depends on and derivesfrom this ancient Chinese masterpiece, even though I am an English speaker andknow only a little of the Chinese language. How is this possible? It isbecause, through its many translations and commentaries on it in otherlanguages, the Yijing has become notonly a treasured Chinese possession,but a book that belongs to all humanity.And if a linguistic purist were to argue, “If you don’t speak Chinese, youcan’t even read, let alone understand the Yijing,”my simple reply would be: “I can read and understand the Bible, even though Idon’t know ancient Hebrew, Aramaic or Greek. The King James Authorised Version of the Bible (1611)is a masterpiece in itself.” Clearly, the crucial importance of translation inthe world of poetry cannot be underestimated.

3. Today, mainly thanks toinformation technology, all the cultural, literary and poetic traditions in theworld are open, accessible and available to all of us, as part of our rightfuland meaningful heritage. So a Chinese poet writing today can be influenced by,say, the Epic of Gilgamesh, JohnKeats, Arthur Rimbaud, Marina Tsvetayeva, Paul Celan, Tomas Tranströmer or GarySnyder – and still maintain and honour his or her full Chinese identity – justas I, an English poet, can be influenced by the Yijing, the Dao de Jing,Homer, Li Bai, Du Fu, Octavio Paz, George Seferis, Emmanuel Levinas and IvanLalić. This contemporary situation of ours, then, is not only subtly andinterestingly complex, but also vital, exciting, and brimming with potential.

4. In this sense we areall both territorial and extra-territorial. Chinese-speakers are to be found inmost major cities in the world. And so are speakers of Greek, Albanian,Swahili, Bengali, and hundreds of other languages, large and small. In theschools of London today, over three hundred languages are spoken. So everyculture, at least potentially, has its diaspora, and every language isinternational. And if that is the case, then so is (its) poetry. The issue, then,of what is native and what is foreignin poetry (alien, other, exotic, strange, etc.)surely needs to be rephrased. An apple tree can grow just as well in an orchardin Sichuan as in Normandy or Illinois or Buenos Aires, and the taste of itsfruit be just as individual and sweet. The history of the world is as full ofcultural reseedings and linguistic transferences as it is of successfulbotanical transplantations.

5. For all these reasons,for a poet to be open to linguistic and literary influences other than thosewithin his or her own ancestral heritage never needs to imply loss of personalor cultural identity, but rather an enrichment and a deepening. All literaturesare part of one literature. All poetries are part of one poetry. All humancultures belong together and cohere. We are all part of the increasingly deepand wide running current that the English Romantic poet William Wordsworthcalled the “music of humanity”.

6. So, whatever its labelmay be, the age both of present-day poetry and of poetry-to-come is irreduciblyand inevitably transcultural, multilingual and international. I call this imaginational.

[责任编辑:冯婧 PN041]

责任编辑:冯婧 PN041

- 0好文

- 0钦佩

- 0喜欢

- 0泪奔

- 0可爱

- 0思考

凤凰文化官方微信

视频

-

李咏珍贵私人照曝光:24岁结婚照甜蜜青涩

播放数:145391

-

金庸去世享年94岁,三版“小龙女”李若彤刘亦菲陈妍希悼念

播放数:3277

-

章泽天棒球写真旧照曝光 穿清华校服肤白貌美嫩出水

播放数:143449

-

老年痴呆男子走失10天 在离家1公里工地与工人同住

播放数:165128

图片新闻